Here's another book review - this one from TAG 60 - Autumn 2002

(the illustration used is from the cover of the second edition of the book)

CELTIC’S PARANOIA – all in the mind?

By Tom Campbell

£11.99 – Fort Publishing

Here's another book review - this one from TAG 60 - Autumn 2002

(the illustration used is from the cover of the second edition of the book)

CELTIC’S PARANOIA – all in the mind?

By Tom Campbell

£11.99 – Fort Publishing

Celtic supporters? Emotional dwarves, right. Crippled from birth by the proverbial chip on both shoulders. Suckled on a diet of quasi-righteous self-pity. Raised in a psychological ghetto of their own construction, hopelessly and helplessly wedded to an underdog mythology. A tribe of moaning malcontents perennially whining their way through a litany of perceived injustice.

Well, maybes aye, maybes naw.

I have a friend who is a ‘keen’ (ie rabid) Celtic supporter. He is a walking encyclopaedia in relation to such matters as Celtic having only been awarded two-thirds the number of penalty kicks as Rangers since 1921. He can instantly call to mind and graphically describe every ‘injustice’ suffered by Celtic in Old Firm games during the whole of the twentieth century. During all the years that I have known him Rangers have, according to him, never beaten Celtic without the assistance of the referee. Even on occasions where the ‘injustice’ has manifestly been the other way, he’s convinced that this is a mere subterfuge to enable the official to more than counterbalance things later on. He’s a mature person. He’s an intelligent person. He’s highly respected in his occupation.

He’s a basket-case.

He’s not unusual. Every reader will recognise the type. There’s thousands of them. As far as I know, Celtic is the only club in world football whose supporters still harbour resentment about multitudes of decisions which occurred in games which took place before any of them were even born. As a result, there is a general perception that Celtic and its supporters are ‘paranoid’.

Tom Campbell’s book tackles this perceived paranoia, and seeks to discover whether there is any basis in fact for the belief, commonly-held among ‘Celtic-minded’ people, that the club has been, and still is, discriminated against and unfairly treated at all levels of the game in Scotland.

This book is meticulously researched and superbly well written. More importantly, it is genuinely enlightening and thought-provoking. As far as I can tell, the author has been reasonably fair-minded in his judgements. However, there are occasions when his Celtic-mindedness breaks through and you have to strip away some rhetoric to get at the facts.

Every single football supporter, whether he supports Celtic, Rangers or Gretna, thinks that his team gets a raw deal from match officials. When that stonewall penalty is denied, when that perfectly good goal is disallowed, when the opposition striker is miles offside without complaint from the ref or his assistants, then we are all roused to a temporary fury, during which homicidal thoughts drift across our brain-pans. Sometimes the sense of injustice is so great that we’re still grumbling about it several hours after the match has ended. In exceptional cases, we phone in to the local radio to vent our spleen, but generally, most of us have pretty well forgotten all about it by the time of the next match.

Not so in the case of Celtic. They are still grumbling about decisions in matches many decades ago. Tom Campbell traces Celtic’s current angst back to an Old Firm match played in 1941 (ie during the war – it was not even an ‘official’ match – this match was taking place at a time when much of Europe was enslaved by Nazi occupation and World War 2 was really starting to hit its genocidal stride). If one performs the rhetoric-stripping which I referred to earlier, the basic facts of the match appear to be these – Rangers first goal was scored from a suspiciously offside position (the suspicion apparently being solely in the mind of the reporter from the ‘Glasgow Observer’ newspaper, which was little more than an early Celtic fanzine, it making no pretence of objective reporting). Shortly afterwards the Rangers goalkeeper (according to the Glasgow (Celtic) Observer) ‘appeared to carry the ball over the line’ when trying to stop a shot, but when no goal was awarded the Celtic supporters became infuriated. Shortly before half-time Celtic were awarded a penalty kick, which the Rangers players protested about. Celtic missed the penalty. At that, Celtic supporters began hurling bottles at the pitch, and fighting. In the second half, the Rangers goalkeeper saved the ball at the feet of a Celtic player. The Celtic player was injured and the Celtic fans thought they should’ve had a penalty, but none was awarded.

All of this sounds fairly routine, and not very much to get your knickers in a twist about, particularly compared with the possible imminent arrival on these shores of the cruellest conquerors in human history. But, hey, this is Glasgow, where there are more elemental forces at work. In the aftermath of the game, the SFA ordered that Celtic Park be closed for a month and that warning notices be posted there, advising spectators of the consequences of future misconduct (Celtic were aggrieved at this because the offending match had actually been played at Ibrox). The SFA also noted and deplored an increase in dissent, particularly on the part of Rangers players, and referees were encouraged to take prompt action. The author quotes a number of prominent journalists and others who had something to say about the affair (he doesn’t detail the allegiance of those commentators, but I think we can make a shrewd guess). For example, the Lord Provost of Glasgow, Sir Patrick Dollan, thought that the SFA’s verdict was “more like Nazi philosophy than British fair play”. So, a fairly measured response from Sir Pat, then.

With the Nazi threat extinguished and the world seeking to return to normality, full-blown hostilities were resumed between the Old Firm when they met in the ‘celebratory’ Victory Cup final of 1946. On this occasion, amongst other things, Celtic alleged that the referee was (a) a Rangers supporter and (b) pished.

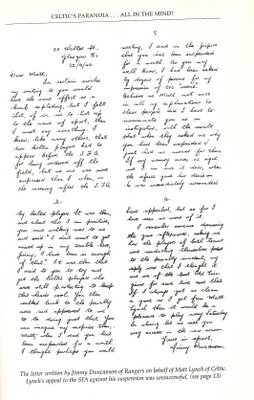

A drunk hun in charge of an Old Firm game. You can’t make it up. Rangers were awarded their statutory dodgy penalty. One Celtic player was sent off for protesting, and another for kicking the ball off the penalty spot before the kick was taken. Then a Celtic supporter dashed onto the field armed with a bottle, apparently intent on striking the referee (or, given the circumstances, perhaps he was offering the ‘inebriated’ official a wee top-up). A bout of stone-throwing followed from the Celtic end, Rangers won, and another chapter was written in the book of injustice for Celtic. The immediate sequel is more interesting than the game, in respect that one of the Celtic players, who had not been sent off, was disciplined by the SFA for allegedly encouraging his colleagues to walk off the pitch in protest at the refereeing decisions. That his punishment was not merited seems amply evidenced by an extraordinary letter of support which he received from his immediate Rangers opponent. A facsimile of the letter is reproduced in the book, and it provides a graphic demonstration of how far standards (both sporting and literary) have fallen in the intervening 60 years. It is quite impossible to imagine any current Rangers player being capable of or willing to pen such a good-humoured and genuinely sporting document. (

see below for reproduction of the letter).

The author breaks off from the minutiae of Old Firm games in, what was to me, a quite astonishing and educational chapter titled ‘The Ghetto Mentality’. The chapter aims to put the experience of Irish Catholic immigrants to Scotland and their descendants into a historical and social context. To that end, the author quotes extensively from a 1923 report by the Church and Nation committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. It has to be appreciated that the General Assembly was a much more powerful and socially influential body in 1923 than it is now. Nowadays a report from the Church and Nation committee would probably be read by a handful of Holy Joes and be completely ignored by everyone else. But in 1923 the ‘Church’ could reasonably claim to speak on behalf of the ‘Nation’. In that context, the report was widely read and was influential across a large part of the indigenous Scottish population. It suggested that Scots were being forced to emigrate from their own country because of the influx of Irish immigrants. It predicted that if this was allowed to continue then “

whole communities in parish, village and town will be predominantly Irish………the great plain of Scotland stretching from Glasgow to Dundee and Edinburgh will be dominated by the Irish race”.

The undesirability of the invaders was made explicit,

“An Irishman never hesitates to seek relief from charity organisations……the Irish are poor through intemperance and improvidence, and they show little inclination to raise themselves in the social scale”. The report argued that the Roman Catholic Church was engaged in “securely establishing a Faith that is distasteful to the Scottish race” and “supplanting the (Scots) by a race that is alien in sympathy and in religion”. It continued, “

Fusion of the Scottish and Irish races will remain an impossibility……it is incumbent on the Scottish people to consider the grave situation in their native land and to devise means to preserve Scotland for the Scottish race…”. All of this bears a striking resemblance to Enoch Powell’s notorious ‘rivers of blood’ speech in the 1960’s where the targeted unwelcome invaders were immigrants from the Indian sub-continent.

The Church and Nation report contains much more in a similar vein, and the reason why the author quotes so lavishly from it (and also the reason why I’ve done the same) is to give some idea of how Irish immigrants were viewed by the Scottish establishment. The language used by the Reverend gentlemen in 1923 would get nowhere near a Church of Scotland document today, but it is undeniable that you can hear echoes of that very language in the chants at modern-day football matches, and much of the committees report could easily be reproduced now, with inflammable intent, in many of the ‘loyalist’ publications on sale at Copland Road on match days.

The suggestion is that the antipathy to the Irish displayed by the Church of Scotland permeated all areas of Scottish life, including, and perhaps most visibly, in football. To get to this point we have to do a quick equation, which involves some generalities, viz :- Irish immigrants are Catholics. All Catholics support Celtic, though not all Celtic supporters are Catholics. That was true in 1923 and it is apparently still true now. Ergo, discrimination against Celtic involves discrimination against Catholics and vice versa.

The other side of that coin is that not all Protestants support Rangers but all Rangers supporters are Protestants. There’s a subtle difference between all Catholics supporting Celtic and all Rangers supporters being Protestants, but frankly, I find both positions equally objectionable. Rangers despicable employment policy now appears to have been addressed. But, until Catholics feel free to support teams other than Celtic then there will continue to be a religious dimension to the game here. I say this from the position of having two (Protestant) brothers who both support Celtic. I would be surprised to find 2 Catholics in the whole of Scotland who support Rangers. Or many more who support any other team. One need look no further for evidence of a continuing ‘ghetto mentality’.

Nevertheless, the author has marshalled his evidence of racial/religious bias persuasively enough to convince me that, at least in an earlier era, such bias did exist. With the waning of the influence of any sort of organised religion amongst the non-Catholics there seems to have been a corresponding diminution in overt discrimination against Celtic football club. That the author recognises this is true is amply illustrated by his own use of a quote from an old edition of TAG where it was said, “There is surely something uniquely deluded about a persecution complex suffered by supporters of a club whose silverware haul is amongst the biggest in the world history of the game”.

When the book moves to the era within the living memory of most TAG readers, then it’s a case of “you pays your money and you takes your choice”. You’re either going to go with the flow and see every ‘controversial’ decision going against Celtic as being part of a continuing ‘Mason in the Black’ conspiracy, or you’re going to wish these people would just shut up and stop whining. The author’s conclusion is that overt bias against Celtic is largely a thing of the past and that it is time for Celtic supporters to rise above the ‘persecution-complex’. This book may go some way to assisting that goal, but I fear that in some cases it will merely serve as a primer and handbook for another generation of ‘we wuz robbed’ moaners.

Whatever its influence, this is a thoroughly impressive piece of work and is highly recommended reading for anyone with an interest in Celtic, whether benevolent, malign or neutral.

Here's another book review - this one from TAG 60 - Autumn 2002

(the illustration used is from the cover of the second edition of the book)

CELTIC’S PARANOIA – all in the mind?

By Tom Campbell

£11.99 – Fort Publishing

Celtic supporters? Emotional dwarves, right. Crippled from birth by the proverbial chip on both shoulders. Suckled on a diet of quasi-righteous self-pity. Raised in a psychological ghetto of their own construction, hopelessly and helplessly wedded to an underdog mythology. A tribe of moaning malcontents perennially whining their way through a litany of perceived injustice.

Well, maybes aye, maybes naw.

I have a friend who is a ‘keen’ (ie rabid) Celtic supporter. He is a walking encyclopaedia in relation to such matters as Celtic having only been awarded two-thirds the number of penalty kicks as Rangers since 1921. He can instantly call to mind and graphically describe every ‘injustice’ suffered by Celtic in Old Firm games during the whole of the twentieth century. During all the years that I have known him Rangers have, according to him, never beaten Celtic without the assistance of the referee. Even on occasions where the ‘injustice’ has manifestly been the other way, he’s convinced that this is a mere subterfuge to enable the official to more than counterbalance things later on. He’s a mature person. He’s an intelligent person. He’s highly respected in his occupation.

He’s a basket-case.

He’s not unusual. Every reader will recognise the type. There’s thousands of them. As far as I know, Celtic is the only club in world football whose supporters still harbour resentment about multitudes of decisions which occurred in games which took place before any of them were even born. As a result, there is a general perception that Celtic and its supporters are ‘paranoid’.

Tom Campbell’s book tackles this perceived paranoia, and seeks to discover whether there is any basis in fact for the belief, commonly-held among ‘Celtic-minded’ people, that the club has been, and still is, discriminated against and unfairly treated at all levels of the game in Scotland.

This book is meticulously researched and superbly well written. More importantly, it is genuinely enlightening and thought-provoking. As far as I can tell, the author has been reasonably fair-minded in his judgements. However, there are occasions when his Celtic-mindedness breaks through and you have to strip away some rhetoric to get at the facts.

Every single football supporter, whether he supports Celtic, Rangers or Gretna, thinks that his team gets a raw deal from match officials. When that stonewall penalty is denied, when that perfectly good goal is disallowed, when the opposition striker is miles offside without complaint from the ref or his assistants, then we are all roused to a temporary fury, during which homicidal thoughts drift across our brain-pans. Sometimes the sense of injustice is so great that we’re still grumbling about it several hours after the match has ended. In exceptional cases, we phone in to the local radio to vent our spleen, but generally, most of us have pretty well forgotten all about it by the time of the next match.

Not so in the case of Celtic. They are still grumbling about decisions in matches many decades ago. Tom Campbell traces Celtic’s current angst back to an Old Firm match played in 1941 (ie during the war – it was not even an ‘official’ match – this match was taking place at a time when much of Europe was enslaved by Nazi occupation and World War 2 was really starting to hit its genocidal stride). If one performs the rhetoric-stripping which I referred to earlier, the basic facts of the match appear to be these – Rangers first goal was scored from a suspiciously offside position (the suspicion apparently being solely in the mind of the reporter from the ‘Glasgow Observer’ newspaper, which was little more than an early Celtic fanzine, it making no pretence of objective reporting). Shortly afterwards the Rangers goalkeeper (according to the Glasgow (Celtic) Observer) ‘appeared to carry the ball over the line’ when trying to stop a shot, but when no goal was awarded the Celtic supporters became infuriated. Shortly before half-time Celtic were awarded a penalty kick, which the Rangers players protested about. Celtic missed the penalty. At that, Celtic supporters began hurling bottles at the pitch, and fighting. In the second half, the Rangers goalkeeper saved the ball at the feet of a Celtic player. The Celtic player was injured and the Celtic fans thought they should’ve had a penalty, but none was awarded.

All of this sounds fairly routine, and not very much to get your knickers in a twist about, particularly compared with the possible imminent arrival on these shores of the cruellest conquerors in human history. But, hey, this is Glasgow, where there are more elemental forces at work. In the aftermath of the game, the SFA ordered that Celtic Park be closed for a month and that warning notices be posted there, advising spectators of the consequences of future misconduct (Celtic were aggrieved at this because the offending match had actually been played at Ibrox). The SFA also noted and deplored an increase in dissent, particularly on the part of Rangers players, and referees were encouraged to take prompt action. The author quotes a number of prominent journalists and others who had something to say about the affair (he doesn’t detail the allegiance of those commentators, but I think we can make a shrewd guess). For example, the Lord Provost of Glasgow, Sir Patrick Dollan, thought that the SFA’s verdict was “more like Nazi philosophy than British fair play”. So, a fairly measured response from Sir Pat, then.

With the Nazi threat extinguished and the world seeking to return to normality, full-blown hostilities were resumed between the Old Firm when they met in the ‘celebratory’ Victory Cup final of 1946. On this occasion, amongst other things, Celtic alleged that the referee was (a) a Rangers supporter and (b) pished.

A drunk hun in charge of an Old Firm game. You can’t make it up. Rangers were awarded their statutory dodgy penalty. One Celtic player was sent off for protesting, and another for kicking the ball off the penalty spot before the kick was taken. Then a Celtic supporter dashed onto the field armed with a bottle, apparently intent on striking the referee (or, given the circumstances, perhaps he was offering the ‘inebriated’ official a wee top-up). A bout of stone-throwing followed from the Celtic end, Rangers won, and another chapter was written in the book of injustice for Celtic. The immediate sequel is more interesting than the game, in respect that one of the Celtic players, who had not been sent off, was disciplined by the SFA for allegedly encouraging his colleagues to walk off the pitch in protest at the refereeing decisions. That his punishment was not merited seems amply evidenced by an extraordinary letter of support which he received from his immediate Rangers opponent. A facsimile of the letter is reproduced in the book, and it provides a graphic demonstration of how far standards (both sporting and literary) have fallen in the intervening 60 years. It is quite impossible to imagine any current Rangers player being capable of or willing to pen such a good-humoured and genuinely sporting document. (see below for reproduction of the letter).

The author breaks off from the minutiae of Old Firm games in, what was to me, a quite astonishing and educational chapter titled ‘The Ghetto Mentality’. The chapter aims to put the experience of Irish Catholic immigrants to Scotland and their descendants into a historical and social context. To that end, the author quotes extensively from a 1923 report by the Church and Nation committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. It has to be appreciated that the General Assembly was a much more powerful and socially influential body in 1923 than it is now. Nowadays a report from the Church and Nation committee would probably be read by a handful of Holy Joes and be completely ignored by everyone else. But in 1923 the ‘Church’ could reasonably claim to speak on behalf of the ‘Nation’. In that context, the report was widely read and was influential across a large part of the indigenous Scottish population. It suggested that Scots were being forced to emigrate from their own country because of the influx of Irish immigrants. It predicted that if this was allowed to continue then “whole communities in parish, village and town will be predominantly Irish………the great plain of Scotland stretching from Glasgow to Dundee and Edinburgh will be dominated by the Irish race”.

The undesirability of the invaders was made explicit, “An Irishman never hesitates to seek relief from charity organisations……the Irish are poor through intemperance and improvidence, and they show little inclination to raise themselves in the social scale”. The report argued that the Roman Catholic Church was engaged in “securely establishing a Faith that is distasteful to the Scottish race” and “supplanting the (Scots) by a race that is alien in sympathy and in religion”. It continued, “Fusion of the Scottish and Irish races will remain an impossibility……it is incumbent on the Scottish people to consider the grave situation in their native land and to devise means to preserve Scotland for the Scottish race…”. All of this bears a striking resemblance to Enoch Powell’s notorious ‘rivers of blood’ speech in the 1960’s where the targeted unwelcome invaders were immigrants from the Indian sub-continent.

The Church and Nation report contains much more in a similar vein, and the reason why the author quotes so lavishly from it (and also the reason why I’ve done the same) is to give some idea of how Irish immigrants were viewed by the Scottish establishment. The language used by the Reverend gentlemen in 1923 would get nowhere near a Church of Scotland document today, but it is undeniable that you can hear echoes of that very language in the chants at modern-day football matches, and much of the committees report could easily be reproduced now, with inflammable intent, in many of the ‘loyalist’ publications on sale at Copland Road on match days.

The suggestion is that the antipathy to the Irish displayed by the Church of Scotland permeated all areas of Scottish life, including, and perhaps most visibly, in football. To get to this point we have to do a quick equation, which involves some generalities, viz :- Irish immigrants are Catholics. All Catholics support Celtic, though not all Celtic supporters are Catholics. That was true in 1923 and it is apparently still true now. Ergo, discrimination against Celtic involves discrimination against Catholics and vice versa.

The other side of that coin is that not all Protestants support Rangers but all Rangers supporters are Protestants. There’s a subtle difference between all Catholics supporting Celtic and all Rangers supporters being Protestants, but frankly, I find both positions equally objectionable. Rangers despicable employment policy now appears to have been addressed. But, until Catholics feel free to support teams other than Celtic then there will continue to be a religious dimension to the game here. I say this from the position of having two (Protestant) brothers who both support Celtic. I would be surprised to find 2 Catholics in the whole of Scotland who support Rangers. Or many more who support any other team. One need look no further for evidence of a continuing ‘ghetto mentality’.

Nevertheless, the author has marshalled his evidence of racial/religious bias persuasively enough to convince me that, at least in an earlier era, such bias did exist. With the waning of the influence of any sort of organised religion amongst the non-Catholics there seems to have been a corresponding diminution in overt discrimination against Celtic football club. That the author recognises this is true is amply illustrated by his own use of a quote from an old edition of TAG where it was said, “There is surely something uniquely deluded about a persecution complex suffered by supporters of a club whose silverware haul is amongst the biggest in the world history of the game”.

When the book moves to the era within the living memory of most TAG readers, then it’s a case of “you pays your money and you takes your choice”. You’re either going to go with the flow and see every ‘controversial’ decision going against Celtic as being part of a continuing ‘Mason in the Black’ conspiracy, or you’re going to wish these people would just shut up and stop whining. The author’s conclusion is that overt bias against Celtic is largely a thing of the past and that it is time for Celtic supporters to rise above the ‘persecution-complex’. This book may go some way to assisting that goal, but I fear that in some cases it will merely serve as a primer and handbook for another generation of ‘we wuz robbed’ moaners.

Whatever its influence, this is a thoroughly impressive piece of work and is highly recommended reading for anyone with an interest in Celtic, whether benevolent, malign or neutral.

Here's another book review - this one from TAG 60 - Autumn 2002

(the illustration used is from the cover of the second edition of the book)

CELTIC’S PARANOIA – all in the mind?

By Tom Campbell

£11.99 – Fort Publishing

Celtic supporters? Emotional dwarves, right. Crippled from birth by the proverbial chip on both shoulders. Suckled on a diet of quasi-righteous self-pity. Raised in a psychological ghetto of their own construction, hopelessly and helplessly wedded to an underdog mythology. A tribe of moaning malcontents perennially whining their way through a litany of perceived injustice.

Well, maybes aye, maybes naw.

I have a friend who is a ‘keen’ (ie rabid) Celtic supporter. He is a walking encyclopaedia in relation to such matters as Celtic having only been awarded two-thirds the number of penalty kicks as Rangers since 1921. He can instantly call to mind and graphically describe every ‘injustice’ suffered by Celtic in Old Firm games during the whole of the twentieth century. During all the years that I have known him Rangers have, according to him, never beaten Celtic without the assistance of the referee. Even on occasions where the ‘injustice’ has manifestly been the other way, he’s convinced that this is a mere subterfuge to enable the official to more than counterbalance things later on. He’s a mature person. He’s an intelligent person. He’s highly respected in his occupation.

He’s a basket-case.

He’s not unusual. Every reader will recognise the type. There’s thousands of them. As far as I know, Celtic is the only club in world football whose supporters still harbour resentment about multitudes of decisions which occurred in games which took place before any of them were even born. As a result, there is a general perception that Celtic and its supporters are ‘paranoid’.

Tom Campbell’s book tackles this perceived paranoia, and seeks to discover whether there is any basis in fact for the belief, commonly-held among ‘Celtic-minded’ people, that the club has been, and still is, discriminated against and unfairly treated at all levels of the game in Scotland.

This book is meticulously researched and superbly well written. More importantly, it is genuinely enlightening and thought-provoking. As far as I can tell, the author has been reasonably fair-minded in his judgements. However, there are occasions when his Celtic-mindedness breaks through and you have to strip away some rhetoric to get at the facts.

Every single football supporter, whether he supports Celtic, Rangers or Gretna, thinks that his team gets a raw deal from match officials. When that stonewall penalty is denied, when that perfectly good goal is disallowed, when the opposition striker is miles offside without complaint from the ref or his assistants, then we are all roused to a temporary fury, during which homicidal thoughts drift across our brain-pans. Sometimes the sense of injustice is so great that we’re still grumbling about it several hours after the match has ended. In exceptional cases, we phone in to the local radio to vent our spleen, but generally, most of us have pretty well forgotten all about it by the time of the next match.

Not so in the case of Celtic. They are still grumbling about decisions in matches many decades ago. Tom Campbell traces Celtic’s current angst back to an Old Firm match played in 1941 (ie during the war – it was not even an ‘official’ match – this match was taking place at a time when much of Europe was enslaved by Nazi occupation and World War 2 was really starting to hit its genocidal stride). If one performs the rhetoric-stripping which I referred to earlier, the basic facts of the match appear to be these – Rangers first goal was scored from a suspiciously offside position (the suspicion apparently being solely in the mind of the reporter from the ‘Glasgow Observer’ newspaper, which was little more than an early Celtic fanzine, it making no pretence of objective reporting). Shortly afterwards the Rangers goalkeeper (according to the Glasgow (Celtic) Observer) ‘appeared to carry the ball over the line’ when trying to stop a shot, but when no goal was awarded the Celtic supporters became infuriated. Shortly before half-time Celtic were awarded a penalty kick, which the Rangers players protested about. Celtic missed the penalty. At that, Celtic supporters began hurling bottles at the pitch, and fighting. In the second half, the Rangers goalkeeper saved the ball at the feet of a Celtic player. The Celtic player was injured and the Celtic fans thought they should’ve had a penalty, but none was awarded.

All of this sounds fairly routine, and not very much to get your knickers in a twist about, particularly compared with the possible imminent arrival on these shores of the cruellest conquerors in human history. But, hey, this is Glasgow, where there are more elemental forces at work. In the aftermath of the game, the SFA ordered that Celtic Park be closed for a month and that warning notices be posted there, advising spectators of the consequences of future misconduct (Celtic were aggrieved at this because the offending match had actually been played at Ibrox). The SFA also noted and deplored an increase in dissent, particularly on the part of Rangers players, and referees were encouraged to take prompt action. The author quotes a number of prominent journalists and others who had something to say about the affair (he doesn’t detail the allegiance of those commentators, but I think we can make a shrewd guess). For example, the Lord Provost of Glasgow, Sir Patrick Dollan, thought that the SFA’s verdict was “more like Nazi philosophy than British fair play”. So, a fairly measured response from Sir Pat, then.

With the Nazi threat extinguished and the world seeking to return to normality, full-blown hostilities were resumed between the Old Firm when they met in the ‘celebratory’ Victory Cup final of 1946. On this occasion, amongst other things, Celtic alleged that the referee was (a) a Rangers supporter and (b) pished.

A drunk hun in charge of an Old Firm game. You can’t make it up. Rangers were awarded their statutory dodgy penalty. One Celtic player was sent off for protesting, and another for kicking the ball off the penalty spot before the kick was taken. Then a Celtic supporter dashed onto the field armed with a bottle, apparently intent on striking the referee (or, given the circumstances, perhaps he was offering the ‘inebriated’ official a wee top-up). A bout of stone-throwing followed from the Celtic end, Rangers won, and another chapter was written in the book of injustice for Celtic. The immediate sequel is more interesting than the game, in respect that one of the Celtic players, who had not been sent off, was disciplined by the SFA for allegedly encouraging his colleagues to walk off the pitch in protest at the refereeing decisions. That his punishment was not merited seems amply evidenced by an extraordinary letter of support which he received from his immediate Rangers opponent. A facsimile of the letter is reproduced in the book, and it provides a graphic demonstration of how far standards (both sporting and literary) have fallen in the intervening 60 years. It is quite impossible to imagine any current Rangers player being capable of or willing to pen such a good-humoured and genuinely sporting document. (see below for reproduction of the letter).

The author breaks off from the minutiae of Old Firm games in, what was to me, a quite astonishing and educational chapter titled ‘The Ghetto Mentality’. The chapter aims to put the experience of Irish Catholic immigrants to Scotland and their descendants into a historical and social context. To that end, the author quotes extensively from a 1923 report by the Church and Nation committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. It has to be appreciated that the General Assembly was a much more powerful and socially influential body in 1923 than it is now. Nowadays a report from the Church and Nation committee would probably be read by a handful of Holy Joes and be completely ignored by everyone else. But in 1923 the ‘Church’ could reasonably claim to speak on behalf of the ‘Nation’. In that context, the report was widely read and was influential across a large part of the indigenous Scottish population. It suggested that Scots were being forced to emigrate from their own country because of the influx of Irish immigrants. It predicted that if this was allowed to continue then “whole communities in parish, village and town will be predominantly Irish………the great plain of Scotland stretching from Glasgow to Dundee and Edinburgh will be dominated by the Irish race”.

The undesirability of the invaders was made explicit, “An Irishman never hesitates to seek relief from charity organisations……the Irish are poor through intemperance and improvidence, and they show little inclination to raise themselves in the social scale”. The report argued that the Roman Catholic Church was engaged in “securely establishing a Faith that is distasteful to the Scottish race” and “supplanting the (Scots) by a race that is alien in sympathy and in religion”. It continued, “Fusion of the Scottish and Irish races will remain an impossibility……it is incumbent on the Scottish people to consider the grave situation in their native land and to devise means to preserve Scotland for the Scottish race…”. All of this bears a striking resemblance to Enoch Powell’s notorious ‘rivers of blood’ speech in the 1960’s where the targeted unwelcome invaders were immigrants from the Indian sub-continent.

The Church and Nation report contains much more in a similar vein, and the reason why the author quotes so lavishly from it (and also the reason why I’ve done the same) is to give some idea of how Irish immigrants were viewed by the Scottish establishment. The language used by the Reverend gentlemen in 1923 would get nowhere near a Church of Scotland document today, but it is undeniable that you can hear echoes of that very language in the chants at modern-day football matches, and much of the committees report could easily be reproduced now, with inflammable intent, in many of the ‘loyalist’ publications on sale at Copland Road on match days.

The suggestion is that the antipathy to the Irish displayed by the Church of Scotland permeated all areas of Scottish life, including, and perhaps most visibly, in football. To get to this point we have to do a quick equation, which involves some generalities, viz :- Irish immigrants are Catholics. All Catholics support Celtic, though not all Celtic supporters are Catholics. That was true in 1923 and it is apparently still true now. Ergo, discrimination against Celtic involves discrimination against Catholics and vice versa.

The other side of that coin is that not all Protestants support Rangers but all Rangers supporters are Protestants. There’s a subtle difference between all Catholics supporting Celtic and all Rangers supporters being Protestants, but frankly, I find both positions equally objectionable. Rangers despicable employment policy now appears to have been addressed. But, until Catholics feel free to support teams other than Celtic then there will continue to be a religious dimension to the game here. I say this from the position of having two (Protestant) brothers who both support Celtic. I would be surprised to find 2 Catholics in the whole of Scotland who support Rangers. Or many more who support any other team. One need look no further for evidence of a continuing ‘ghetto mentality’.

Nevertheless, the author has marshalled his evidence of racial/religious bias persuasively enough to convince me that, at least in an earlier era, such bias did exist. With the waning of the influence of any sort of organised religion amongst the non-Catholics there seems to have been a corresponding diminution in overt discrimination against Celtic football club. That the author recognises this is true is amply illustrated by his own use of a quote from an old edition of TAG where it was said, “There is surely something uniquely deluded about a persecution complex suffered by supporters of a club whose silverware haul is amongst the biggest in the world history of the game”.

When the book moves to the era within the living memory of most TAG readers, then it’s a case of “you pays your money and you takes your choice”. You’re either going to go with the flow and see every ‘controversial’ decision going against Celtic as being part of a continuing ‘Mason in the Black’ conspiracy, or you’re going to wish these people would just shut up and stop whining. The author’s conclusion is that overt bias against Celtic is largely a thing of the past and that it is time for Celtic supporters to rise above the ‘persecution-complex’. This book may go some way to assisting that goal, but I fear that in some cases it will merely serve as a primer and handbook for another generation of ‘we wuz robbed’ moaners.

Whatever its influence, this is a thoroughly impressive piece of work and is highly recommended reading for anyone with an interest in Celtic, whether benevolent, malign or neutral.

This is the letter referred to above - click to enlarge - it's well worth reading in full

This is the letter referred to above - click to enlarge - it's well worth reading in full

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home